- Accueil

- Conversations écologiques

- essais réservation

- Economie de carburant

- News letters

- Le louveteau de Bagnes

- Le Mystère du Fregnoley

- météo

- Les glaciers

- idées de courses

- Textiles promowear

- Matos montagne

- Liste des 4000 m des alpes

- indice de regel

- Formation des Alpes

- nouvelle de montagne

Le Glacier de Valsorey

After a few hours of hiking off the beaten path, I hear its whisper...

A faint breath, almost dying, growing louder as I approach the monster.

The wild torrent, gushing from its lair, showers me with fine, heavy, sandy droplets, carried by the warm breath of the valley.

Its story... But what story?

A glacier is inert, lifeless, without a past… and above all, without a future.

A glacier dies slowly, silently, leaving no trace. In solitude… a slow burn.

No one cares about a glacier.

Except the mountaineer who suddenly disappears into one of its gaping jaws, to feed its legend.

The glacier of Valsorey, though — he’s a sorcerer. And he spoke to me.

It’s the first time a glacier has ever spoken to me!

Probably because I had decided to take my time. To listen with my eyes. To attune my ear to its whisper.

To seek the dying remnants hidden under two meters of rubble.

To watch the streams slipping down a bone-dry moraine.

To hear the falling rocks echo in the silence of the valley.

To finally accept the infernal cry of the torrent crashing against the void of the world.

The valley of Valsorey deserves more than human memory.

Sitting on a carpet of yellow, welcoming flowers, facing the Grand Combin,

I listened to the glacier’s memories resonate in the depths of my soul.

Here begins the historical tale of the King of Valsorey.

👉 See also the precipitation and temperature records of the past 120 years at the Grand-Saint-Bernard Pass,

and their influence on the future evolution of the Valsorey Glacier.

– Hey Valsorey. Who are you, exactly?

I’m the Valsorey Glacier, perched at the top of the valley that bears my name, just above Bourg-Saint-Pierre.

I cover an area of 1.90 km² and stretch about 3 kilometers long. I was born around 95,000 years ago.

And as you’ve probably noticed, it takes over three hours of walking to reach my funeral bed.

90,000 years ago, I extended far beyond Geneva, mingling with all my Alpine cousins — from the Aletsch Glacier to the Rhône.

My closest neighbor, the Grand Combin Glacier, towered over me… but as they say, I still did my part.

Today, I’m dying… but it’s not the first time.

I’m about the same size as I was around the year 1000 AD. And believe me, I’ve seen my share of upheavals.

– What an incredible story! But what’s your place in today’s world?

You know, little city-dweller… history is long, but your memory is short. It barely stretches past a few decades.

I may be made of ice, but my memory spans thousands of years.

Your neurons might just melt trying to keep up. Are you ready?

– Oh, I see… the dying one mocks me. You don’t seem in any position to act all eco-centric…

Still, this adventure feels both distant and strangely close. I may be just a little one from below, but I long to understand the history of the great ones above —

though “great” no longer seems like the right word, my friend…

The last glaciation began around 100,000 years ago.

My maximum reach dates back about 21,000 years, when I stretched all the way to Lyon, in neighboring Gaul.

If you don’t mind, I’ll skim over the stretch from 100,000 BC to the year zero — a time when I remained in good health, mostly stable, though stirred now and then by the moods of the sun and Earth’s elliptical dance.

Between the years 500 and 900 AD, my sweating looked much like today’s.

My torrent was already wreaking havoc in the Valsorey valley during hot summers.

Temperatures in the Entremont region were comparable to those of the 1990s.

Your scientists call this the “Medieval Warm Period.”

A bizarre, decadent end to the Roman era — warm and deadly for us glaciers, who retreated visibly, day by day.

About 900 years ago, my ice began to swell like a balloon.

Growth often brings strange shapes, and for me, it meant reconnecting with old neighbors:

– the Tseudet Glacier, flowing down the north face of the Vélan,

– and the Sonadon Glacier, pouring from the south face of the Grand Combin de Grafeneire.

Together, we sculpted imposing moraines.

The steeper glaciers pushed and compressed the flatter ones, like me.

Wedged between Tseudet on the left and Sonadon on the right, I patiently built the right-bank moraine —

which eventually rose over 80 meters high.

On the left side, the solid rock of the Vélan kept my enthusiasm in check,

but its paler trace is still visible today.

– You mean those moraines are over 800 years old?

Let me finish, little conqueror of the pointless.

In just 100 years, I lost much of my grandeur.

I shrank down to today’s size… or almost.

But that didn’t last long.

Around 1500, a global cooling began — likely due to a period of low solar activity, known as the Maunder Minimum.

The Little Ice Age, as you call it, wasn’t so much due to colder temperatures, but rather to a dramatic increase in snowfall.

Winters were snowy, summers wet and cold.

Result? A positive mass balance — and a spectacular advance of my tongue.

Each year, heavy snowfall up high pushed me further down the valley.

My glacial front shoved ahead tons of rocks, earth, and rubble, building the moraines you still see today.

Imagine: in just a century, I grew by a kilometer in length and gained a hundred meters in

thickness.

Impressive, right?

Back then, the people of the Entremont valley suffered greatly.

In 1693 and 1694, peasants fled to lower, warmer lands — sometimes as far as Vaud.

Leave or die. Many died.

And those who survived… died of boredom among the Vaudois! Obviously…

The cold starved the cities, as waves of peasants arrived in search of food.

Supplies ran low everywhere.

The glaciers of Mont Blanc told me that nearly 1.7 million French people died in those two years —

as many as during World War I. Can you believe that?

– That’s chilling… and very cold up on the moraine!

Glacial winters and miserable summers plunged Europe into despair.

Peasants roamed the roads, begging, hoping to find food.

Sheep died along the paths.

The carcasses of dogs, horses, and other beasts were eaten — even when rotting.

Suicides and even cannibalism weren’t rare.

Epidemics — especially typhoid — spread like wildfire.

The winter of 1709–1710 is still infamous.

Wine froze in the king of France’s glass.

Temperatures dropped to -25°C in the lowlands.

That winter alone caused 200,000 to 300,000 deaths from cold and hunger.

And don’t forget — Europe had only just emerged from the Black Death (1347–1351),

which reduced the population from 69 to 40 million.

The Little Ice Age arrived at the worst possible moment.

And yet… in 1540, Europe endured a catastrophic drought.

Forests burned, rivers dried up, and people died of thirst…

But I? I kept advancing… quietly.

In England, the River Thames froze regularly.

Starting in 1608, they even held “frost fairs” on the frozen waters.

In the cities, nobles and the bourgeois laughed and played.

But in the countryside, peasants died.

In 1815, the colossal eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia was the most powerful in recorded history.

It’s estimated to have thrown nearly 200 billion tons of ash into the upper atmosphere.

The thick veil of dust and gases blocked part of the sun’s rays, triggering a global climatic cooling — temporary, yes, but brutal.

Disasters followed one after another.

Because glaciers, you see, don’t just invade pastures —

they destroy chapels and villages, they trigger deadly floods by damming entire valleys.

In 1595, the Giétro Glacier devastated the Drance Valley after its lake burst:

140 people died.

Two years later, the collapse of the Hohmatten Glacier in Valais killed 81 more.

In 1633, the flood from Lake Mattmark, above Saas-Fee, tore through the valley all the way down

to Visp.

And in 1818, the Giétroz Glacier struck again, killing over 40 people in another outburst.

In Valais, Lake Märjelen, beside the Aletsch Glacier, emptied violently in 1813,

1820, and 1828.

In the Protestant canton of Bern, they resorted to exorcisms — in Grindelwald, in

1719, then again in 1777.

By 1850, the Ried and Gorner Glaciers

(Valais) were even officially banished during their last major advance.

All across the Alps, people prayed and pleaded.

They summoned bishops when the ice grew too close to their homes, their fields, or their roads.

Those were my golden years.

My neighbors — Sonadon and Tseudet — had merged into one with me.

And despite a few squabbles, we were able to descend once more below the great drop, down to around 2,200 meters.

The farmers watched us with fear.

I strutted with pride.

My torrent was quieter than it is today, and the summer nights so cool that my ice glistened under the sun.

The moraines were barely visible; the snow, almost permanent, kept its whiteness all year long.

– Wow! You must have been magnificent... And then?

You already know what happened next, little brainless human.

Our decline began... at the same time as your so-called "Medieval Optimum."

But you didn’t know it yet.

Your ancestors discovered oil.

And with it came cheap energy.

Your world spun out of control.

Your consumption exploded.

You gorged yourselves on luxury.

You humans are masters of invention —

but always to make life easier.

And above all, to make money.

You shamelessly drained the bowels of this dying planet.

Now, my tears flow in the Valsorey torrent.

We watched you — helpless — trapped in your valleys, incapable of changing course.

We sent you signs:

– glacial lakes collapsing,

– sudden floods,

– moraines gasping under each falling stone.

The permafrost is melting.

Soon, your mountain huts will collapse.

– With all due respect, your retreat has also allowed for stunning new landscapes: flowers, biotopes, lakes, greenery. The cows now graze higher. Tourism

is thriving. And I’m convinced our politicians will protect you for centuries to come!

By 2050, we won’t emit any more CO₂, and you’ll be able to live again… You’re much older than me — you’ll surely outlive me, right?

You brainless little twit.

My death is inevitable.

I lose 3 to 5 meters of thickness every year.

Even if you stopped emitting CO₂ tomorrow, I would still die.

Temperatures rise every year.

I sweat from every pore.

You wouldn’t even want my ice in your pastis anymore.

Look at the furious torrent beneath your feet —

that’s my vitality, vanishing to power your turbines.

Let me laugh... and be realistic:

I’m already dead.

My rotting corpse will disappear beneath collapsing moraines.

My skin reeks of decay.

I cling desperately to the northwest faces, like a shipwrecked fool to a buoy.

And instead of dying with dignity, the city-dwellers will come mock me with selfies.

We’ve become gladiators condemned before we even enter the arena.

From King of Valsorey, I will become a servant to the queens of Hérens...

– Uh... …………………

Hmm!

Could that be a glimmer of lucidity in that nearly empty head of yours?

– Maybe… But how can you be so sure that your death is near?

Haven’t you heard of climate disruption?

At the Grand-Saint-Bernard, temperatures have already risen +2.7°C since the

1800s.

Every summer, scorching heat falls on us like a furnace.

Autumn drags on endlessly.

It snows later, and melts away sooner.

And worst of all — there’s less and less rain.

If there’s no snow up top, there’s no advance.

Melting accelerates. Renewal is gone.

The thinner I get, the more the surrounding moraines heat up, warming my surface.

With less weight, they collapse onto my fragile body.

But don’t worry — your species will suffer too.

Human population might drop by half by the end of the century.

You look like a pathetic old fool.

Look at yourself in the mirror!

Ha! Ha! Ha!

– You’re right… even if I hate to admit it. I keep hoping for some optimism.

Every summer I watch you, and I see the decline. But... what can I do?

You can’t do anything.

No need to glue your hands to the roads.

No need to fight with climate deniers.

No need to insult those who fly.

You’re here.

You’re listening to me —

and that’s already something.

My death won’t change anything.

Your awareness will come too late.

These coming years will be my agony.

I’m tired.

Tomorrow night will be warm, all the way up to the summit of the Vélan.

At 3,700 meters, it will still be nearly 10°C.

I’ll feel the mild southwest wind gnawing away at every inch of my skin.

Desert dust, now common, will leave a red veil on my white surface —

and that will accelerate my melting even more.

If you’re sad...

write my story.

But don’t be disappointed if no one reads it.

Writing only feeds the writer.

City-dwellers now only read on their gadget-thingies.

They no longer have time to read.

They still have time to look, but no longer to read.

Writing feeds the dreamer.

Images feed the lazy.

Video feeds… the absent.

My future? I have none.

But at least, I know it.

You, on the other hand, still believe in a future —

without knowing your end.

Well… look at the sky. It’s getting dark.

Time to head back to your sweetheart,

before you end up skewered on that useless ice axe of yours.

Description du Roi

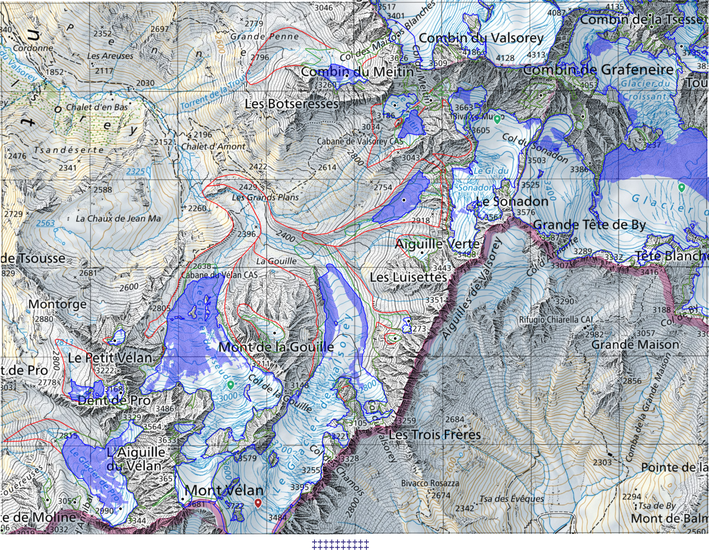

Red line: glacier in 1850 / green line: 1973 / blue line: 2016 / black line: 2022

Shaded areas: glacier covered with debris. Approximately 2 meters thick at most.

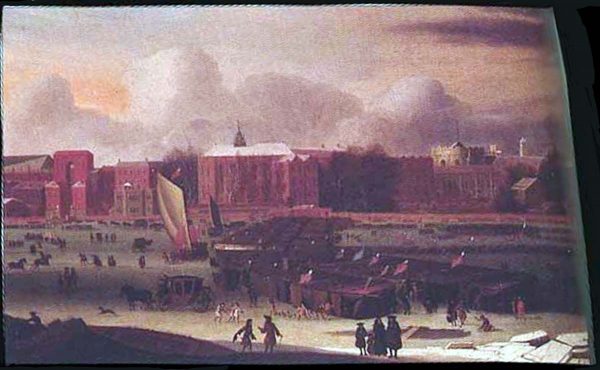

Very interesting image of the Valsorey Glacier from 1910 or 1911.

The Sonadon Glacier was already dead at lower altitudes, fully exposed to the south, but Valsorey was thriving.

The glacier's edge reached nearly to the top of the moraine.

Its lower limit was likely between 2,200 and 2,320 meters, around the level of the current icefall — or even slightly below — which suggests the

glacier was close to its maximum extent at that time.

The glacier was approximately 1,200 meters longer than it is today.

Valsorey Hut, built in 1901, with a shingle roof and 25 beds.

Section of the Swiss Alpine Club (SAC) – La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Note personnelle:

N'oublions pas que le les glaciers des Alpes se sont reformés dans des conditions fabuleuses lors du Petit âge glaciaire (PAG) entre 1450 environ et 1820. Auparavant nos glaciers avaient plus ou moins les mêmes proportions qu'aujourd'hui.

Sans vouloir dénigrer le dérèglement climatique du tout qui accélère clairement la fonte depuis la fin du 20 ème siècle. Je pense qu'il est important de savoir que les glaciers actuels n'ont rien à faire à des altitudes de 2500 mètres en face Sud. Du reste ils fondent depuis le milieu des années 1800 alors que les températures étaient environ 1,5° plus froides qu'aujourd'hui. (statistiques des températures au col du Grd-St-Bernard)